How to read nutrition labels: the gamer guide to a valuable life skill

Key points

Disclaimer

This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace the advice of your doctor. Esports Healthcare disclaims any liability for the decisions you make based on this information.

The information contained on this website does not establish, nor does it imply, doctor-patient relationship. Esports Healthcare does not offer this information for diagnostic purposes. A diagnosis must not be assumed based on the information provided.

A basic, yet extremely poorly understood health and life skill is how to read nutrition labels. Nutrition labels can be misleading, and many companies will take advantage of nomenclature and listing guidelines to make their product(s) seem healthier, more appealing, or—in some cases—to hide the fact that they are down-right unhealthy.

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides a 132-page PDF called the Food Labeling Guide which outlines every detail of food and drink labeling. Fortunately, we’ve summarized those details for you here in a far more consumer-friendly manner.

The basics of how to read nutrition labels

According to the FDA, food labeling is required on most prepared foods, while labeling for items such as produce or fish is not required.

Food labeling is required for most prepared foods, such as breads, cereals, canned and frozen foods, snacks, desserts, drinks, etc. Nutrition labeling for raw produce (fruits and vegetables) and fish is voluntary.[1]

Food Labeling and Nutrition via FDA.gov

The FDA has specific requirements for label placement and information that is required for the primary display panel (PDP), usually the front of the product label with the product name, size and weight, and the information panel which will provide the nutrition label and ingredient list. For this post, we will focus more heavily on the information panel.

Primary display panel (PDP) information

For food and drink products, the PDP is essentially the “front cover” of the item for sale. When you see an item on a shelf, you should be seeing the PDP which will include the product name and will usually include a picture of the product or clear packaging to show what you’re buying.

According to FDA regulations, the PDP must also include the net quantity of contents either by weight (for solids or semi-solids) or fluid measurement (for liquids) and must be listed in both empirical (ounces, pounds, fluid ounces) and metric (grams, kilograms, milliliters, liters).[2]

It is important to note that this measurement is based on the consumer item only and is absent of packaging weight such as boxing, wrapping, and other containers. The FDA also outlines specifics for font size, display area, and other formatting details in their Food Labeling Guide.

Information panel: nutrition label and ingredient list

The FDA has strict and specific guidelines for nutrition labels and ingredient lists on the information panels of foods and drinks. Some specifics include font size, color coordination, and intervening material (in other words, information not required by law).

Ultimately, these rules are in place to provide all required information in an easy-to-read block of information. Sadly, this easy-to-read block can still be confusing and misleading.

Making sense of the ingredient list

As previously stated, ingredient lists are part of food and drink labels and are required, by law, on most prepared food and drink items. While the ingredient list is just that—a list of what is inside—the order of the list is important.

It is mandatory to provide a list of ingredients in descending order based on each ingredients’ weight (or volume). Therefore, the first ingredient is the predominant ingredient. For example, in many drinks, the first ingredient is water.

This fact becomes exceedingly important when you buy foods or drinks that claim they are a certain type of food. For example, if you buy a can of baked beans, you should expect that the first ingredient is, in fact, beans. Likewise, if you purchased tomato soup, you should expect the first ingredient to be tomatoes.

Be wary of food or drink items in which the first few ingredients include sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, or artificial additives. Most often, these items are highly processed and are considered to be unhealthy and poor quality.

Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA)

The FDA requires ingredient lists to include major allergens, and it is mandatory to provide specific identification for severe allergens such as dairy, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, soybeans, fish and Crustacean shellfish, wheat and gluten. According to the FDA, these foods result in 90% of all food allergies.[3]

The nutrition label and Nutrition Facts

The nutrition label is required either on the primary display panel (PDP) or the first available space to the right of the PDP. The nutrition label must also include the ingredient list and the name and address of the manufacturer, packer, and distributor. Additionally, the nutrition label must be presented in a square space regardless of the package shape.[2]

There are many other formatting details regarding font size, line breaks, and coloring that are not necessary for you to understand how to read nutrition labels; these details can be found on the FDA’s Food Labeling Guide.

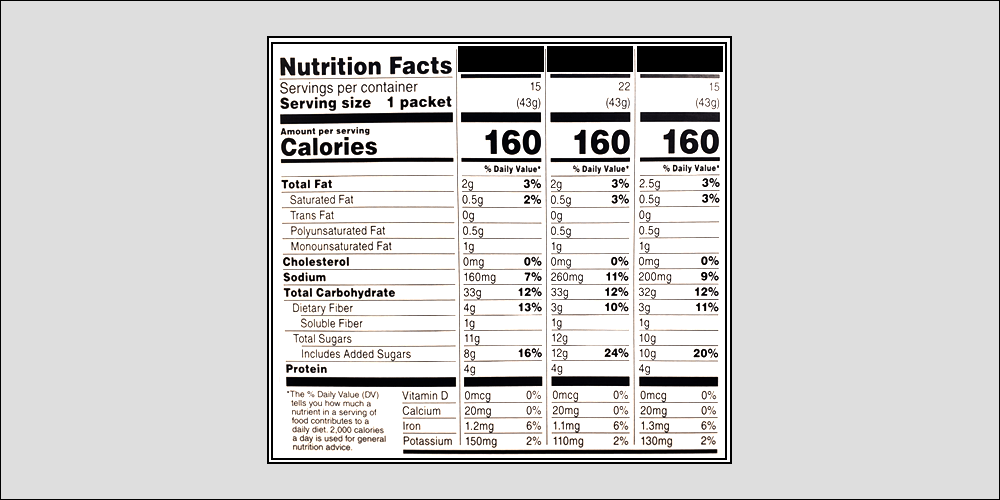

According to the FDA, the following information must be provided on the Nutrition Facts in this precise order:

- Serving Size and Servings Per Container

- Calories, including Calories from Fat

- Total Fat, including Saturated Fat and Trans Fat

- Cholesterol

- Sodium

- Total Carbohydrate, including Dietary Fiber and Sugars

- Protein

- Micronutrients: Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Calcium, Iron

Additional information such as unsaturated fats, added sugars, and other vitamins and minerals are not required unless they are added, separately, or if their presence has a related nutrient content or health claim (e.g. calcium and Vitamin D for bone health).

Serving information

The Serving Size is the suggested single volume of consumption. On nutrition labels, this must be listed with measurements in both empirical (ounces, cups, etc.) and metric (grams). The label also must provide the Servings Per Container which is how many servings are present in the entire package.

Calories

Calories are the measurement of a food or drink’s energy. Technically, the listed Calorie count is in kilocalories (denoted by a capital letter “C” when written without the kilo- prefix). Calories in consumables come from dietary fat, carbohydrates, protein, and alcohol.

Calories listed on labels are most often rounded figures. For labels consisting of 50 Calories or less, the number is rounded to the nearest 5 g increment (e.g. 47 would be rounded down to 45). For Calorie counts greater than 50, the number is rounded to the nearest 10 g increment (e.g. 96 to 100).

For reference, each macronutrient provides a certain number of Calories. The approximate values per 1 gram are:

- Fat: 9 Calories

- Carbohydrate: 4 Calories

- Protein: 4 Calories

- Alcohol: 7 Calories

Calories from Fat

Calories from fat must be explicitly listed on nutrition facts labels where Calories from carbohydrates and protein are not required to be listed, specifically. One gram of dietary fat is approximately 9 Calories. Therefore, the Calories from fat is equal to your Total Fat multiplied by nine.

Dietary fat

The Total Fat in a product is the amount of dietary fat, in grams, in one serving of the product. This volume includes saturated fat, unsaturated fats—which can exist as monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fat—and trans fat. Current FDA regulations mandate listing the amount of saturated fat and trans fat while unsaturated fat listings remain voluntary.

Fat listings, like Calorie listings, are also rounded values. Below 0.5 g of fat will be listed as 0 g total fat. For quantities between 0.5 g and 5 g, the value is rounded to the nearest 0.5 g increment. For quantities above 5 g, the value is rounded to the nearest whole number increment.

Saturated Fat

The term “saturated” is in reference to the hydrogen atoms in the molecular structure of the fat. Fatty acids are molecules that consist of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. A saturated fat is one that has no double bonded carbons and therefore contains highest volume of hydrogen atoms possible.

Although necessary as part of a balanced diet for optimal health, higher-than-recommended amounts of saturated fat have been correlated with increased blood cholesterol and greater risk for cardiovascular disease.

Common sources of saturated fat include red meat, whole-fat dairy products, butter, ice cream, coconut oil, and palm oil.

Trans Fat

Trans Fat is a synthetic (made in a lab) dietary fat that has the reverse molecular configuration (cis- vs. trans- configuration) of naturally occurring fatty acids. Trans fats do not exist in nature! The FDA does not have an established recommended daily value for trans fat; research has found trans fats to be terribly unhealthy. It is best to find foods where the trans fat quantity is zero.

Due to labeling guidelines, trans fat may exist in a quantity greater than 0 g but less than 0.5 g, and the label will still read 0 g. Thus, it is important to read the ingredient list. If you see ingredient such as “shortening” or “partially hydrogenated vegetable oil,” then trans fat exists in the product.

Monounsaturated Fat

The FDA does not require labeling for monounsaturated fats; however, some companies will still elect to include these values. Monounsaturated fats are named based on a single double bond in the molecular structure which reduces (or desaturates) the total hydrogen atoms by 2.

Monounsatured fat helps to reduce systemic, chronic low-grade inflammation which can exacerbate underlying conditions and increase the likelihood of disease. Monounsaturated fats are also cardioprotective; they have been shown to improve blood lipid profiles and reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.[6]

Common sources of monounsaturated fats include peanuts and peanut butter, tree nuts and their nut butters, avocados, extra virgin olive oil, canola oil, safflower oil, sunflower oil, and sesame oil.[6]

Polyunsaturated Fat

Like its counterpart in monounsaturated fat, labeling Polyunsaturated Fat is not a required by the FDA, but some companies will still elect to include it. Polyunsaturated fats are named based on the presence of two or more double bonds in their molecular structure which reduces (desaturates) the total hydrogen atoms by 4 or more.

Animal-sourced polyunsatured fats are the most healthy (e.g., fish and fish oils). Plant-sourced polyunsaturated fats are still healthy, too; however, the greatest health benefit has been recognized via consumption of polyunsaturated fats from fish and fish oils. Fish oil, like monounsaturated fat, has been shown to reduce systemic, chronic low-grade inflammation and reduce cardiovascular risk.[7]

Common sources of polyunsaturated fats include walnuts, sunflower seeds, flaxseeds or flaxseed oil, salmon, mackerel, herring, tuna, corn oil, soybean oil, and safflower oil.[7]

Dietary fat: weight vs. nutrition

If you are buying ground beef, ground turkey, or ground chicken, the front of the label will give you a measurement of fat compared to the entire product. Common fat contents of ground meat products include 80/20, 85/15, or 93/7, where the smaller number is the percentage of fat that exists in the packaging.

Beef that is described as 80% lean / 20% fat indicates that 20% of the product’s weight is fat. This is an incredibly important distinction because the percent weight of fat is not equivalent to the percent of Calories.

For example, a 4 ounce serving of 80/20 ground beef equates to 0.8 ounces of total fat (20% of 4 oz is 0.8 oz). The same 4 ounce serving of 80/20 ground beef has ~290 calories including 23 g total fat and 20 g protein.

Recall the approximate Calories per macronutrient, and multiply 23 g by 9 Calories and 20 g by 4 Calories. The result is >200 Calories from fat and ~80 Calories from protein (note: there are 0 carbohydrates in ground beef).

If you divide the amount of Calories from fat by the total Calories, you will notice nearly 70% of your Calories are from fat! So, the front of the label for 80/20 ground beef reports 20% fat by weight; however, nutritionally, 80/20 ground beef is actually 70% fat!*

*This does not indicate ground meat products are unhealthy. Rather, it is an explanation to help you understand the nuances of food labeling. If you count Calories and/or track macronutrients, do not rely on the percentage of fat by weight; instead, use the Nutrition Label and check Calories and macronutrient breakdowns.

Cholesterol

The Cholesterol on a nutrition label is a measure of the cholesterol (a fat-based molecule created by living cells) that exists in a particular food or drink. However, cholesterol from food/drink sources is generally not absorbed to be utilized in the human body. Your cells make their own cholesterol created by the fatty acids you consume.

Sodium

Sodium is an electrolyte mineral necessary for fluid balance and nerve conduction. Sodium is found in most consumables in the form of sodium-chloride, or table salt.

Generally speaking, it is unlikely to have a sodium insufficiency or deficiency in the United States due to the natural presence of sodium in animal products and the addition of sodium as a preservative for foods and drinks with a shelf-life. Fortunately, drinking appropriate amounts of water will limit many potential ill-effects of high sodium consumption.

Carbohydrates

Total Carbohydrate is the total volume of all carbohydrates (which includes sugar and dietary fiber); one carbohydrate provides approximately 4 Calories.

Carbohydrates, similar to fats, are molecules consisting of carbon chains with hydrogen and oxygen. Carbohydrates are used for shorter, higher intensity energy needs and are therefore the preferred energy system for working muscles.

It is important to monitor your consumption of carbohydrates because of their effect on blood glucose and insulin. Carbohydrates, unlike fats, will increase your blood glucose levels; in response to increased blood glucose, your body will release insulin (absent of type-1 diabetes or other metabolic ailments).

However, large, rapid, and/or prolonged increases in insulin may lead to insulin resistance—where your cells response to insulin is suppressed and utilization of blood sugar for energy becomes more difficult. Thus, blood sugar may rise to dangerous levels and glucose begins to store as fat.[8]

Insulin resistance is the foundation of type-2 diabetes and a major factor in obesity and other ailments including nerve damage and cardiovascular disease.

Dietary Fiber

Dietary fiber is a carbohydrate complex that aids in digestion. Fiber can be either soluble—which dissolves in water—or insoluble—which does not dissolve.

Soluble fiber creates a gel-like substance which can help regulate cholesterol and blood sugar. Insoluble fiber will cause an increase in the fluid volume in your bowel helping regulate bowel movements.[5]

Carbohydrates with a larger percentage of dietary fiber will result in a slower, less intense blood glucose spike. Likewise, your insulin response will also be slower and less intense. These carbohydrates, found commonly in vegetables, are considered to be healthier options.

Sugars

Sugars listed on labels, according to FDA regulations, are a measurement of total volume of monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, galactose) and disaccharides (sucrose [table sugar], lactose, and maltose). Monosaccharides are the simplest form of sugar and cannot be broken down further. Disaccharides can be broken down into individual monosaccharides.

Sugars that are not mono- or disaccharides (e.g. processed forms, such as high-fructose corn syrup) must be listed in the ingredient list separately. Only the 6 mono- and disaccharides listed above can be grouped into the “sugar” listing.

Carbohydrates with a higher percentage of sugars will result in a faster, more intense blood glucose spike. Likewise, your insulin response will also be faster and more intense. These carbohydrates, often processed, are considered to be less healthy options.

Includes (x) g added sugars

When additional sugar is added to a food or drink, it is listed below the subheading for Sugars as “Includes (x) g added sugar” to differentiate from naturally occurring sugar (e.g. natural sugar in fruits). Foods that are 100% all-natural will not have added sugar.

Protein

The protein listed on a label is simply the volume of protein, in grams. This is not specific to amino acid complex. Proteins, like fats and carbohydrates, are macronutrients meaning your body can break these molecules down for energy.

Generally, protein is not your body’s preferred energy source. Rather, protein is most commonly used for building muscle and other body structures and to transport fats (and cholesterol) via the blood stream.*

*Dietary fat (and cholesterol) cannot dissolve in water, and blood plasma is mostly water. Instead, your body uses lipoproteins to transport these molecules via blood since protein can dissolve in a water-based fluid.

Vitamins and minerals

The FDA only mandates that the percentage of Reference Daily Intake (RDI) for Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Calcium, and Iron are listed on a food or drink label. It is not a requirement to list the weight (e.g. milligrams or international units [IU]) of these four ingredients. All other vitamins and minerals are described as voluntary.

In addition to the four nutrients listed above, the FDA states that manufacturers may add vitamins and minerals for which the RDI has been established. Again, these values—if listed—only need to be listed by the percentage of RDI and not by weight.

The FDA makes specific note of the mineral potassium. If potassium is listed, it is to be listed immediately following sodium on the main portion of the label. All other voluntary vitamins and minerals are to be listed following the four required vitamins and minerals (see The nutrition label and Nutrition Facts above for the appropriate order of nutrition facts).

Nutrient claims

You may have seen a food or drink label with a phrase such as “fat free,” “low sodium,” or “reduced calories,” among others. These relative terms—free, low, and reduced—are described as nutrient claims, and there are specific guidelines for each claim depending on the ingredient.

These words (or their synonyms, listed below) are used when comparing a particular ingredient in a given product to the Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed (RACC).

The RACC is a value established by the FDA for 139 food product categories. According to the FDA, these values “represent the amount of food customarily consumed at one eating occasion.” Serving sizes are based on the RACC.

For the complete table, see Appendix A on the FDA’s Food Labeling Guide. An abbreviated reference is listed in the table, below. Please note, the comparisons listed in the table are based on the RACC for similar foods for the given ingredient.

For example, the Sodium content in a serving of potato chips vs. other potato chips and snack foods.

| Free | Low | Reduced | |

| Calories | less than 5 | 40 Cal or fewer | > 25% fewer |

| Total Fat | less than 0.5 g | 3 g or less | > 25% less |

| Saturated Fat | less than 0.5 g | 1 g or less | > 25% less |

| Cholesterol | less than 2 mg | 20 mg or less | > 25% less |

| Sodium | less than 5 mg | 140 mg or less | > 25% less |

| Sugars | less than 0.5 g | May not be used | > 25% less |

- Free: synonyms include “no” and “zero”

- Low: synonyms include “little” and “few”

- Reduced: synonyms include “less” and “fewer”